Pika Research and Conservation at Craighead InstituteAmerican pikaThe American pika (Ochotona princeps) is the smallest member in the rabbit family that includes rabbits and hares. Pikas are plant generalists but habitat specialists in that they require cool microclimates to regulate their body temperature. Pikas are distributed throughout the western United States and are found mainly in moist subalpine and alpine habitats that are dominated by talus slopes. They are extremely well adapted to montane environments, but are sensitive to climatic extremes and temperatures above 80oF can be lethal to pikas in as little as six to eight hours. To stay cool, pikas will stay in rock crevices or under large boulders until the ambient temperature cools. Pikas can also inhabit non-alpine environments at lower elevations that include lava fields and mining areas. In these areas the temperatures tend to be much higher and pikas must adjust their foraging behaviors to cooler times of the day and utilize the cool microclimates for longer periods of time.

Pikas do not hibernate and remain active all winter long. They store large “haypiles” or stores of vegetation in the late summer and fall that they cache and will utilize all winter long. In Montana pikas typically range between 5,500-10,500 feet in elevation and inhabit rocky talus or boulder fields throughout the western part of the state. |

Effects of Climate Change on Pika Populations

Photo by A. Craighead

Climate change and its effects on all species may be one of the most difficult challenges to be faced in the twenty-first century. The most notable changes will be felt at high latitudes and at the poles. As humans, we will be able to mitigate some of the climate challenges through migration, innovative technologies and change in political policies. Plant and wildlife species on the other hand will be limited in their ability to withstand climate change. Species will either adapt by migrating latitudinal or altitudinal within their ranges, finding microclimate refugia that are buffered from extremes, or perish.

One species that is threatened by climate change is the pika (Family Ochotonidae). Pikas are highly sensitive to warm temperatures and are physiologically unable to survive if the temperature exceeds a certain threshold. Therefore they serve as excellent indicators of a changing climate. These denizens of high alpine environments are already feeling the heat. Populations are being extirpated in the United States’ Great Basin of Nevada, and in the Tian Shan mountains of China. Evidence suggests that increased temperatures and a changing climate are to blame.

One species that is threatened by climate change is the pika (Family Ochotonidae). Pikas are highly sensitive to warm temperatures and are physiologically unable to survive if the temperature exceeds a certain threshold. Therefore they serve as excellent indicators of a changing climate. These denizens of high alpine environments are already feeling the heat. Populations are being extirpated in the United States’ Great Basin of Nevada, and in the Tian Shan mountains of China. Evidence suggests that increased temperatures and a changing climate are to blame.

Help Support our Pika Research & Adopt a Pika Today!

Pika Survey

Montana Pika Survey & Citizen Science

Photo by Becka Barkley

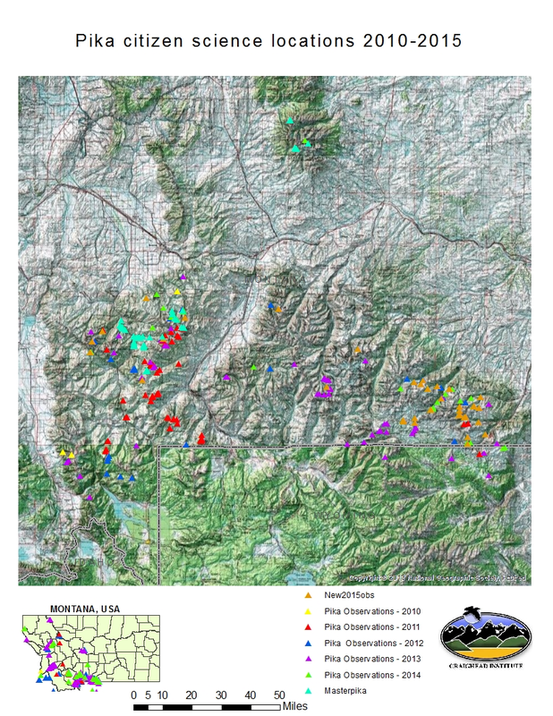

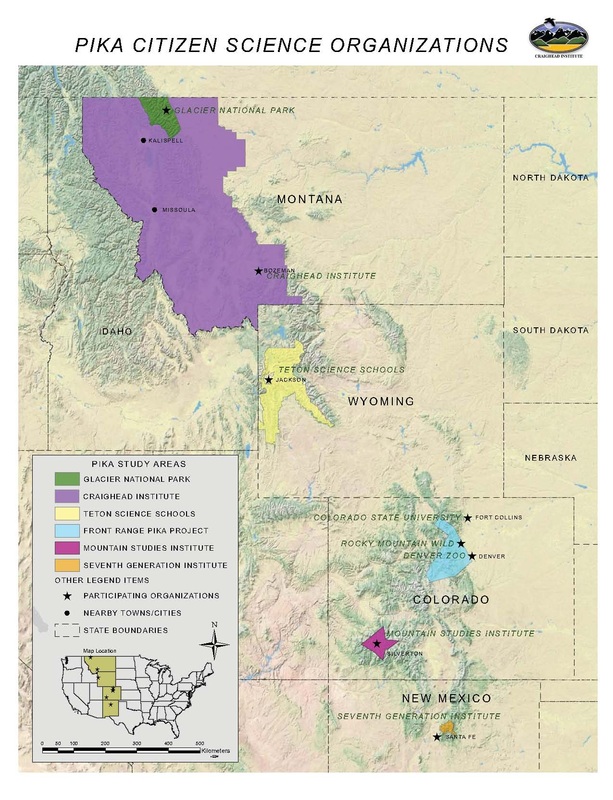

The Montana Pika survey began in 2010, its goal was to engage citizens to provide GPS locations of pikas in Montana by filling out a simple pika survey and collecting spatial data on pikas in the field. The program was modeled after the very successful Teton Science Schools pika project survey which began in 2009. Accurate locations can be gathered with the use of a handheld GPS, smart phone application (app) or using Google earth. Locations are then mapped and the information catalogued to provide a simple yet biologically relevant data base to be used by researchers and agency personnel.

Pikas are an ideal species to engage the public in citizen science, they are charismatic, easy to identify, amenable to being watched and are found in spectacular alpine settings. Only a limited amount of training is required to have volunteers ready to participate in scientific research and assure that quality data are collected. Similar projects throughout the Rocky Mountains are providing crucial data on pika habitat and distribution to researchers that will help guide conservation efforts in the future. Gathering data from Montana will fill in data gaps needed for the Northern Rockies.

The first year, April Craighead, Craighead Institute's wildlife biologist, targeted agency personnel (Forest Service, National Park Service and interested non-profit organizations) by offering educational presentations. We had limited success in the first year with four observers providing data for five new pika locations. Since then she has conducted more presentations and training sessions to agency personnel as well as citizen scientists. This strategy continues to pay off and by the end of 2015 we had a total of 372 new pika locations since 2010. Many of these locations have never been previously recorded or there had not been any records in many decades. We have a core group of dedicated volunteers that hike many a mile to find pikas and the success of this program depends on their time, energy and passion. I’m truly grateful to you all! If you are interested in becoming a volunteer, please contact me.

Pikas are an ideal species to engage the public in citizen science, they are charismatic, easy to identify, amenable to being watched and are found in spectacular alpine settings. Only a limited amount of training is required to have volunteers ready to participate in scientific research and assure that quality data are collected. Similar projects throughout the Rocky Mountains are providing crucial data on pika habitat and distribution to researchers that will help guide conservation efforts in the future. Gathering data from Montana will fill in data gaps needed for the Northern Rockies.

The first year, April Craighead, Craighead Institute's wildlife biologist, targeted agency personnel (Forest Service, National Park Service and interested non-profit organizations) by offering educational presentations. We had limited success in the first year with four observers providing data for five new pika locations. Since then she has conducted more presentations and training sessions to agency personnel as well as citizen scientists. This strategy continues to pay off and by the end of 2015 we had a total of 372 new pika locations since 2010. Many of these locations have never been previously recorded or there had not been any records in many decades. We have a core group of dedicated volunteers that hike many a mile to find pikas and the success of this program depends on their time, energy and passion. I’m truly grateful to you all! If you are interested in becoming a volunteer, please contact me.

Pika photos taken by volunteers in Montana

|

Citizen science has a long history of providing quality data on species presence/absence, population trends, and phenology. Long standing programs such as Audubon’s Christmas Bird count and the North American Lilac Blooming program have provided data on birds since 1900 and lilac blooming phenological data since 1956. Both of these programs have provided scientists, managers, and interested citizens information on species distribution and changes in relation to climate for more than a century. Resource managers and scientists utilize these data along with information from other scientific studies to identify population trends, monitor changes in the environment and develop management policies. More recently many new citizen science programs have been developed utilizing the power and accessibility of the internet, providing outdoor and educational opportunities to a broader audience and a new generation of outdoor enthusiasts. In an era of shrinking budgets and the decline of nature values well thought out citizen science programs are more important than ever.

Only a limited amount of training is required to have volunteers ready to participate in this scientific research and assure that quality data are collected. While many of these programs sound idyllic and glamorous it is important to remember that the goal of the program is to provide accurate quality data that can be used by a whole host of users. Volunteers need to be trained on how to recognize pikas either by sound, visually, scat or haypile remains and if there is any ambiguity about the data, it needs to be discarded. Volunteers also need to be ready to work with researchers to make sure that all of the relevant data is captured. Are there pikas in the Bridger Mountains?

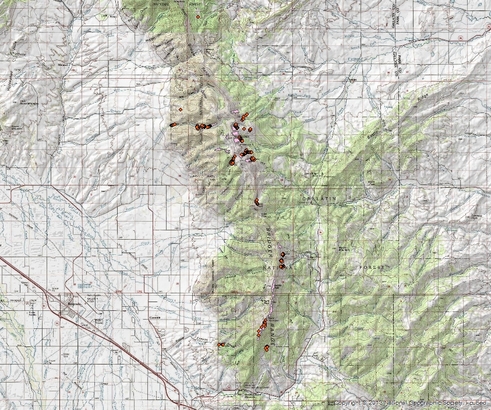

The Bridger Mountains are situated just north of Bozeman, it is a relatively small range, running north to south and is approximately 26 miles long and has adequate talus habitat. This area is highly frequented by outdoor enthusiasts both winter and summer with numerous trails and a ski area. The Bridger’s are also an important corridor for migrating wildlife and contains abundant predator and prey species. There is anecdotal evidence of pikas in the Bridger Mountains but no historical evidence through collecting records (MSU and UM mammalian specimens). This seems odd since the Bridger’s are so accessible and collectors in the twentieth century were prolific at obtaining specimens of pikas and other species such as yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris) and bushy-tailed woodrats (Neotoma cinerea) in similar areas. With the help of private donors I began surveying the Bridger’s in 2011, 2013 for pikas and I was able to survey the entire range in 2015 with the help from our intern Max Lewis. We recorded data for 162 survey points and found no evidence of any pika sign. Conservation Implications After surveying the Bridger’s I don’t think there are currently any extant pika populations. The talus on the west side of the range is typically large and without a sustaining meadow component. The talus on the east side is more suitable, mainly limestone but there does not appear to be current or past populations. Other talus obligates like yellow-bellied marmots and bushy tailed woodrats were found throughout the range indicating that the habitat does support animals that rely on talus. Pikas may have inhabited the Bridger Range at one time perhaps right after the last ice age, populations could have declined due to disease or changes in plant communities and finally became extinct. If they existed into the 20th century, warming temperatures in the past few decades may have driven pikas extinct however we have found no evidence of old pika sign (pika sign can remain in the environment for long periods of time, perhaps decades). Due to long distances to other pika populations they were never able to recolonize. Survey points within the Bridger Mountains

|

Changes in alpine plant communities

Photo by C. Eldridge

As climate changes, plant communities will respond by moving to different elevations or latitudes in response to new temperature and climate regimes. For many species this shift will be upward in elevation and northward in latitude. This trend is already being documented in the United States and in Europe as plant communities are slowly moving in response to climate change.

Pikas are plant generalists feeding on a wide array of grasses, graminoids, shrubs and trees however not all plants contain the same nutritional value. Grasses tend to be eaten sooner and forbs tend to be stored and consumed later in the winter. Changes in plant communities due to climate change could change the nutritional balance of plant species that pikas forage on thus lowering the overall fitness of pikas. These changes are already being recorded in high alpine areas in Colorado.

Resurveying of plant communities began in 2010 with approximately nine long term sites being resurveyed near Emerald Lake in the Hyalite Mountains. In 2011, 12 more sites were resurveyed and that data is still being analyzed. In 2012, we collected data on 1,116 plant plots on the western side of the canyon. In 2013 we will finish the rest of the sampling and begin analysis to determine if these plant communities have changed since they were originally surveyed in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. These multiple comparisons will allow researchers to determine if plant communities are beginning to change due to climate change in alpine areas in the Gallatin Mountains.

Pikas are plant generalists feeding on a wide array of grasses, graminoids, shrubs and trees however not all plants contain the same nutritional value. Grasses tend to be eaten sooner and forbs tend to be stored and consumed later in the winter. Changes in plant communities due to climate change could change the nutritional balance of plant species that pikas forage on thus lowering the overall fitness of pikas. These changes are already being recorded in high alpine areas in Colorado.

Resurveying of plant communities began in 2010 with approximately nine long term sites being resurveyed near Emerald Lake in the Hyalite Mountains. In 2011, 12 more sites were resurveyed and that data is still being analyzed. In 2012, we collected data on 1,116 plant plots on the western side of the canyon. In 2013 we will finish the rest of the sampling and begin analysis to determine if these plant communities have changed since they were originally surveyed in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. These multiple comparisons will allow researchers to determine if plant communities are beginning to change due to climate change in alpine areas in the Gallatin Mountains.

Monitoring active pika locations in southwestern Montana

This project is an extension of the work that Dr. Chris Ray began in 1998 with pikas at Emerald Lake in the Gallatin Mountains. April was interested in continuing a monitoring project in a nearby location and historic records from researchers indicated that pikas are located within Gallatin Canyon at much lower elevations (5,500 ft). April began to wonder if pikas at these lower elevations were still extant and how temperatures differ for these pikas at lower elevations. April began systematic surveys for pikas in Gallatin Canyon from approximately MP 63 (Hellroaring trailhead) to MP 47.5 at Big Sky and along adjacent drainages at higher elevations. By the end of 2012, she located 44 active pika locations in that study area and will be monitoring pika activity for the next few years. Pika data collected included GPS location, talus measurements and pika activity.

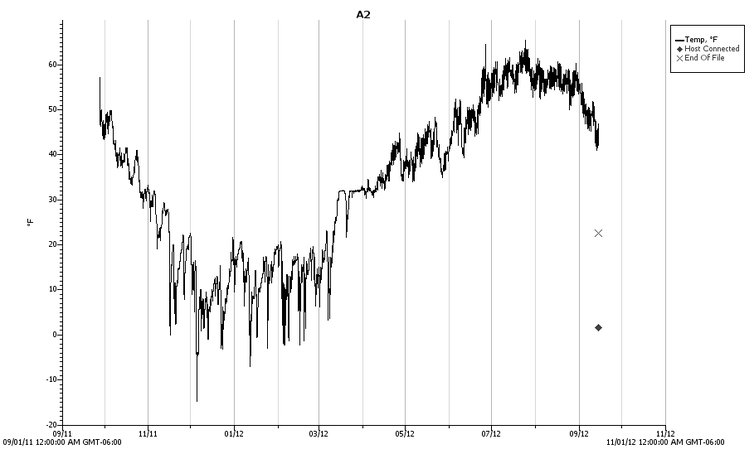

A total of eighteen temperature data loggers were placed to record under talus temperatures as well as ambient temperatures. In some of these locations April has three years of subsurface talus temperatures. Below is what a typical temperature profile looks like at some of these low elevation sites. This data logger was placed near an active haypile approximately 20 cm below the talus near Swan Creek and recorded temperatures throughout 2011-2012. This pika withstood wildly varying temperatures, especially in winter months with the coldest temperature recording -14.7 o F on December 5, 2011. During the summer, temperatures below the talus reached into the high 60’s.

A total of eighteen temperature data loggers were placed to record under talus temperatures as well as ambient temperatures. In some of these locations April has three years of subsurface talus temperatures. Below is what a typical temperature profile looks like at some of these low elevation sites. This data logger was placed near an active haypile approximately 20 cm below the talus near Swan Creek and recorded temperatures throughout 2011-2012. This pika withstood wildly varying temperatures, especially in winter months with the coldest temperature recording -14.7 o F on December 5, 2011. During the summer, temperatures below the talus reached into the high 60’s.

Thanks in large part to the following organizations, foundations, businesses, and individuals who have supported our pika research programs:

April Craighead presenting to a sold-out REI workshop

Charlotte Martin Foundation The Cinnabar Foundation The Harris Foundation The Hudoff Families The Mountaineers Foundation Montana Import Group Northern Lights Trading Company REI Bozeman Rockford Coffee Wild Joes Coffee Yellowstone Club Community Foundation |