Dr. Frank C. Craighead

Frank Cooper Craighead, Jr. was born in Washington, D.C. on August 14, 1916. His parents were Dr. Frank C. Craighead, Sr. and Carolyn Johnson Craighead. Frank, Sr. was a forest entomologist working for the Department of Agriculture, and Carolyn was a biologist technician. It's impossible to tell Frank's story without including his identical twin brother, John. They did everything together for many years, and the family history is full of stories about their ability to know what the other one was thinking, to finish sentences for each other, and to come to each other's defense. Their younger sister, Jean, was born three years after Frank and John and shared many of their early adventures.

Frank spent his childhood in the Washington, D.C. area. At the time the Potomac River was still pure enough to drink, and he and John spent every spare minute fishing, canoeing, and learning the names of plants and animals along the river. Frank credited his father with instilling an appreciation for knowledge, and for showing him how to observe and understand the natural world. As teenagers, Frank and John were fascinated with birds of prey. This interest led them to learn the practice of falconry, and they were among a handful of people who revived the ancient sport in the United States. Frank and John were also tricksters; stories of their many practical jokes are still fondly told at family gatherings.

Frank spent his childhood in the Washington, D.C. area. At the time the Potomac River was still pure enough to drink, and he and John spent every spare minute fishing, canoeing, and learning the names of plants and animals along the river. Frank credited his father with instilling an appreciation for knowledge, and for showing him how to observe and understand the natural world. As teenagers, Frank and John were fascinated with birds of prey. This interest led them to learn the practice of falconry, and they were among a handful of people who revived the ancient sport in the United States. Frank and John were also tricksters; stories of their many practical jokes are still fondly told at family gatherings.

Birds of Prey

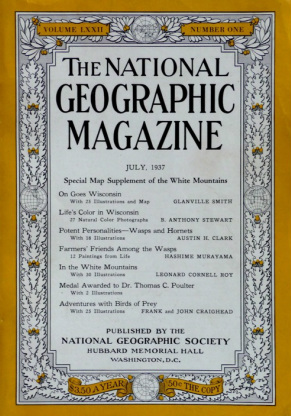

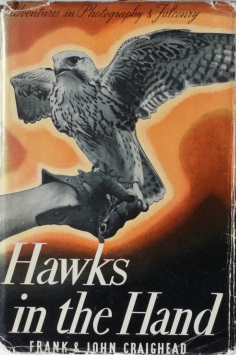

In the summer of 1934, just after high school, Frank and John drove West in a 1928 Chevrolet with several of their friends, photographing and capturing hawks and falcons. They drove on dirt roads all the way, pulling over at night to camp. During this trip they first saw Jackson Hole, and they visited with naturalists Olaus and Mardy Murie. The spectacular beauty of Wyoming remained with them through subsequent travels, and they promised themselves they would return some day to live near the Tetons. Parts of this trip were described in their first magazine article, "Adventures with Birds of Prey", for the National Geographic Magazine, in 1937. "Hawks in the Hand" was the first book that Frank and John wrote, published in 1939. It contains stories of their early adventures while learning falconry and photography.

Frank and John graduated with A.B. degrees in Science in 1939 from Pennsylvania State University, where they both excelled on the wrestling team. As identical twins, Frank and John were notorious for substituting for each other in classes while one of them went off to fish or look for hawks, but they would never admit to doing the same switch on dates. They both went on to the University of Michigan for M.S. degrees in Ecology and Wildlife Management in 1940. That same year an Indian Prince named K.S. "Bapa" Dharmakumarsinjhi read their falconry article in the National Geographic Magazine, and invited them to visit him in India. The National Geographic Society paid Frank's and John's expenses and supplied them with cameras and film, and they sailed to India on a passenger liner for a nine month stay with Bapa. They wrote an article and made a film about this visit, both titled "Life With an Indian Prince." These were the last days of the rule of Maharajahs in India, and the last days of Indian falconry on a grand scale. Their visit was curtailed by the outbreak of World War II, and they caught passage home on a freighter in 1941.

Frank and John graduated with A.B. degrees in Science in 1939 from Pennsylvania State University, where they both excelled on the wrestling team. As identical twins, Frank and John were notorious for substituting for each other in classes while one of them went off to fish or look for hawks, but they would never admit to doing the same switch on dates. They both went on to the University of Michigan for M.S. degrees in Ecology and Wildlife Management in 1940. That same year an Indian Prince named K.S. "Bapa" Dharmakumarsinjhi read their falconry article in the National Geographic Magazine, and invited them to visit him in India. The National Geographic Society paid Frank's and John's expenses and supplied them with cameras and film, and they sailed to India on a passenger liner for a nine month stay with Bapa. They wrote an article and made a film about this visit, both titled "Life With an Indian Prince." These were the last days of the rule of Maharajahs in India, and the last days of Indian falconry on a grand scale. Their visit was curtailed by the outbreak of World War II, and they caught passage home on a freighter in 1941.

Writing the Navy's Manual for "How to Survive on Land and Sea"

The United States' entry into the war interrupted Frank's education in wildlife. Frank and John attended the University of Michigan in 1941 and 1942 while they worked toward their Ph.D. degrees. They also organized and conducted an outdoor living course for training military pre-inductees. He and his brother were literally going out the door to join the Army's 10th Mountain Division when the U.S. Navy asked them to set up a survival training program. They became Lieutenants in USNR Aviation Training, where they organized and administered survival training for pilots and sailors stranded in unfamiliar country, and they wrote the Navy's manual, "How to Survive on Land and Sea."

They were based in Pensacola, Florida. To add to their knowledge of survival in the tropics, Frank and John taught and trained with the Navy's core group of instructors in tropical ecosystems in the Marshall Islands and the Philippines. Toward the end of the war, Frank and John trained agents of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services -- later to become the CIA) in survival tactics, and they were scheduled to be dropped into areas behind Russian lines when the war fortunately came to an end.

They were based in Pensacola, Florida. To add to their knowledge of survival in the tropics, Frank and John taught and trained with the Navy's core group of instructors in tropical ecosystems in the Marshall Islands and the Philippines. Toward the end of the war, Frank and John trained agents of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services -- later to become the CIA) in survival tactics, and they were scheduled to be dropped into areas behind Russian lines when the war fortunately came to an end.

Post-war PhD's and Family

After the war, Frank returned to Jackson Hole, where he and John bought 14 acres of land from John Moulton on Antelope Flats, near Moose. At the time, the boundary of Grand Teton National Park was on the other side of the Snake River, to the west. Frank and Esther moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, while Frank returned to his studies at the University of Michigan. He and John had received fellowships from the Wildlife Management Institute, and they earned their Ph.D.s in 1949, despite a legacy of practical jokes at their professors' expense. Their Ph.D. dissertations were published as a book, titled "Hawks, Owls, and Wildlife."

Meanwhile, John Craighead had married Margaret Smith, a mountain climber and daughter of a Grand Teton Park ranger. Frank and Esther, and John and Margaret built identical log cabins on their property in Moose, and began families. While Frank was completing his various field studies during the late 1940s and early 1950s, he and Esther had three children - Lance, Charlie, and Jana - all born in Jackson at the old log cabin.

Meanwhile, John Craighead had married Margaret Smith, a mountain climber and daughter of a Grand Teton Park ranger. Frank and Esther, and John and Margaret built identical log cabins on their property in Moose, and began families. While Frank was completing his various field studies during the late 1940s and early 1950s, he and Esther had three children - Lance, Charlie, and Jana - all born in Jackson at the old log cabin.

The Desert Game Range & Atomic Tests

In 1950, Frank and John were survival consultants to the Strategic Air Command, and in 1951 they organized survival training schools for the Air Force at Mountain Home and McCall, Idaho. From 1953 to 1955 Frank conducted classified defense research. His log home in Moose wasn't winterized, so the family lived in various places around the Jackson Hole valley, including stays on the Murie Ranch, the old Budge house in Wilson, and a house in Jackson. Frank and John went their separate ways in the early 1950s, when John accepted a permanent position with the University of Montana and Frank decided to work outside of Academia. From 1955 to 1957 he managed the Desert Game Range outside Las Vegas, Nevada, for the USFWS. This was the era of nuclear testing and Frank had great concerns about the effects of radiation, but his efforts to measure and document radiation levels on the refuge were not encouraged by the federal government. Family photographs of the time show the kids playing in the yard, with a mushroom cloud in the background.

Grizzly Bears in Yellowstone

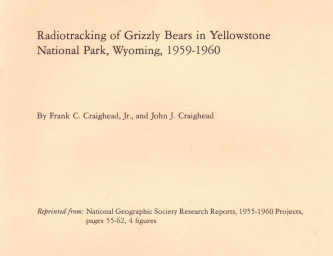

During 1959, Frank and John's careers merged again. At the request of Yellowstone National Park, they began a 12-year study of grizzly bears. Frank would drive from Pennsylvania, arriving in Yellowstone early in the spring and staying until late in the fall when the bears denned. Esther waited until the kids were out of school and then drove to Moose for the summer. In late August she would load up the station wagon and drive back to Boiling Springs. By 1966 the long cross-country drives had become too much. Frank added indoor plumbing to his cabin on Antelope Flats, and he and Esther moved to Moose permanently.

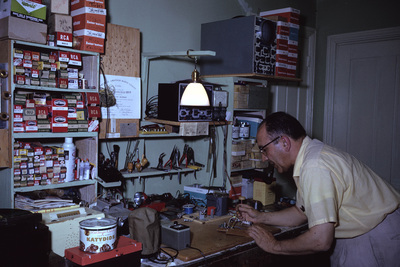

Developing Radio-tracking of Wildlife

Perhaps Frank's greatest contribution to the grizzly bear study, and to the science of wildlife ecology, was his leadership in developing and using radio transmitters. He first worked on this with an old friend from Pennsylvania, Hoke Franciscus, whose experience as a ham radio operator enabled the two to build some simple transmitters. Frank then enlisted another friend, electrical engineer Joel Varney of Philco-Ford, who developed the first working large-mammal radio collars. Several years later, with Joel's expertise, they modified U.S. Navy navigation buoys to develop the first animal satellite transmitters. The radio-tracking technology the Craigheads pioneered in the 60's has now been used on every continent and applied to species as diverse as humpback whales and honeybees.

Pioneering Wild Animal Tranquilization

Frank and the rest of the grizzly bear study crew then developed field techniques to attach the collars and track the movements of the bears. Their pioneering efforts to learn which combination of drugs was best for immobilization had some interesting moments. Here in the video below, a large grizzly bear quickly recovers from the drug as the researchers attempt to finish collecting the data they need.

During the years of the grizzly bear study, Frank and John found time to publish a Peterson Field Guide on wildflowers, write four articles for National Geographic magazine, make two National Geographic Television specials, "Grizzly" and "Wild Rivers," and four lecture films.

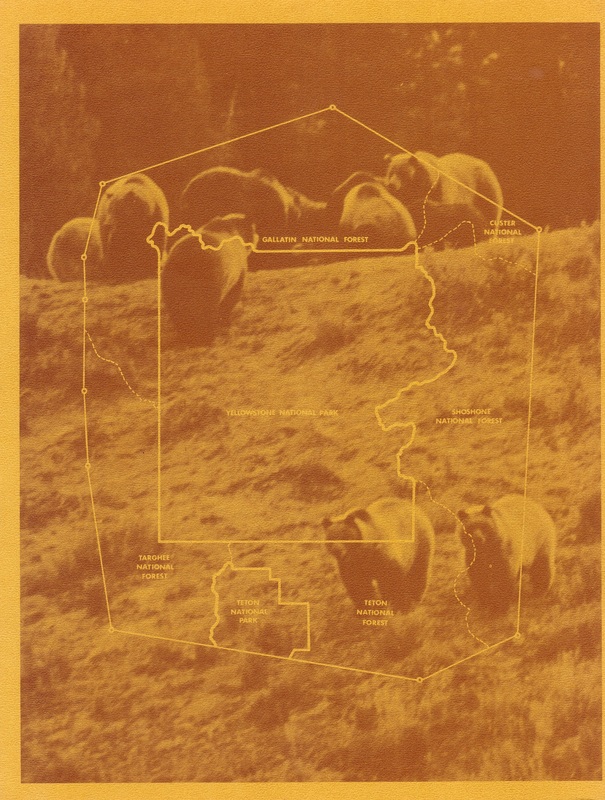

The Concept of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

By radio-tracking the grizzlies of Yellowstone National Park, the Craigheads discovered that bears often moved outside of the Park and onto surrounding National Forests. The figure below shows the outer edge of their grizzly locations. Based on these data, the Craigheads introduced the concept of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This concept became central to bear management in the region and is still used 40 years later.

Writing the National Wild & Scenic River Act

Frank also became active in the conservation of wild rivers, and much of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 came verbatim from his writings.

Frank and John Craighead’s involvement with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act began in the early 50’s when they were conducting survival training from a base in McCall, Idaho. Part of the training involved wilderness raft trips, using surplus rafts that they had used during World War II survival training, to float the Salmon and Snake rivers. This gave them a deep appreciation of wild rivers which contrasted greatly to the rivers of their youth; rivers like the Potomac near Washington DC which had become increasingly polluted and crowded with recreationists.

In 1957, Frank was working in Washington DC for the US Forest Service, helping to design an agency response to a newly identified need. John was involved in the fight to stop the Army Corps of Engineers dam at Spruce Park on the Middle Fork of the Flathead. They wrote an article for Naturalist magazine in which Frank described a system of river classification including wild, semiwild, semiharnessed, and harnessed rivers. He reasoned that once rivers were categorized people would see the scarcity of quality streams and realize the need to protect them. John wrote that rivers were needed as benchmarks for comparison of environmental change: “Rivers and their watersheds are inseparable, and to maintain wild areas we must preserve the rivers that drain them”. They both felt that wild rivers were needed for recreation and education of future generations.

In 1958 Congress created the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission to prepare the nation’s first thorough study of recreation needs. Its mandate was that certain rivers of unusual scientific, aesthetic, and recreational value should be allowed to remain in their free-flowing state and natural setting without man-made alteration. The Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, asked Frank Craighead (then at USFWS) to prepare a paper on river classification, and asked the Secretary of Agriculture (Orville Freeman) to organize a wild and scenic rivers study team. Frank created his own organization, the Outdoor Recreation Institute, which later became a non-profit organization, the Environmental Research Institute.

In 1959 the US Senate formed a ‘Select Committee on National Water Resources’ hoping to thwart Eisenhower administration policies fighting federal dams (creeping socialism according to Eisenhower). At a field hearing in 1959 the Craighead brothers called for a system of federally protected rivers. Ted Schad was director of the committee’s staff. The Select Committee’s report proposed that certain streams be preserved in their free-flowing condition “because their natural scenic, scientific, aesthetic, and recreational values outweigh their value for water development and control purposes now and in the future.” This became the federal government’s first major proposal for a national rivers system.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service reported that some rivers are most valuable if left unaltered, and Interior officials wrote to the ‘Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs’ that the integrity of natural free-flowing streams might be preserved in the face of the water-control onslaught if conscientious planning were applied.

In 1961 President Kennedy called for protection of the Current River during his conservation message to the Senate Select Committee on National Water Resources. In 1962 the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission recommended the creation of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. President Kennedy endorsed it, and Stewart Udall established it on April 2, 1962 by Administrative Order.

In 1963 Gaylord Nelson introduced a bill to make the St. Croix a ‘national river’. In 1964 the Ozark National Scenic Riverways and parts of the Current River were designated as the first national rivers.

In 1964 the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission collected a list of 650 rivers for consideration. That was reduced to 70, and 22 were selected for detailed field study. These included the Big Hole, Madison, Upper Missouri, and Yellowstone rivers. The conservationists with the Wilderness Society (formed in 1930) – Stewart Brandeborg, Howard Zahniser, and others – had also talked about a system of wilderness rivers. The wilderness concept had 40-year gestation period. With Wild and Scenic Rivers it was much faster; just a few years. President Johnson wanted new legislation and Stewart Brandeborg told him about the wild and scenic river idea and he said “That sounds great, get it ready.”

In 1964 the first bill was introduced which was called the Wild Rivers Act, Congress later broadened this to include ‘scenic’ and ‘recreation’ rivers. In 1965 President Johnson called for a rivers bill in his State of the Union Address. Frank Church, Senator from Idaho, sponsored the bill in the Senate. It passed the Senate in 1965 but got no further.

Over several years 16 different Wild and Scenic bills were introduced. Stewart Udall championed them. In 1968, an election year, any action on the bill was delayed. Its supporters had little hope for anything that year, but the house committee finally released the bill and the House voted in favor of it 265-7. The Senate approved it on October 2, and it was signed into law by President Johnson.

This was 14 years after the Craigheads had begun their work to envisioned it. They had been working on a National Geographic television special: "Wild River" that they hoped would generate public support for the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The bill, however, became law before the film was even released!

There are Three Types Of Wild & Scenic Rivers

• “Wild” rivers — vestiges of primitive America

• “Scenic” rivers — free of impoundments, with shorelines or watersheds still largely

primitive and undeveloped, but accessible in places by roads

• “Recreational” rivers — readily accessible by road or railroad, may have some development

along their shorelines, and may have undergone some impoundment or diversion

in the past

A Wild & Scenic designation:

• Protects a river’s “outstandingly remarkable” values

and free-flowing character Protects existing uses of the river.

• Prohibits federally-licensed dams, and any other federally-assisted water resource project

if the project would negatively impact the river’s outstanding values

• Establishes a quarter-mile protected corridor on both sides of the river

• Requires the creation of a cooperative river management plan that addresses

resource protection, development of lands and facilities, user capacities, etc.

The first eight Wild and Scenic Rivers were designated in the Act itself. Funds were appropriated for land acquisition for each:

Clearwater, Middle Fork, Idaho, $2,909,800;

Eleven Point, Missouri, $10,407,000;

Feather, Middle Fork, California, $3,935,700;

Rio Grande, New Mexico, $253,000;

Rogue, Oregon, $15,147,000

St. Croix, Minnesota and Wisconsin, $21,769,000;

Salmon, Middle Fork Idaho, $1,837,000; and

Wolf Wisconsin, $142,150.

There are now 156 National Wild and Scenic Rivers. The North, South and Middle Forks of the Flathead River were designated in 1976 and are managed by the US National Park Service and US Forest Service. No rivers had been designated in Montana since that time until August 2nd, 2020, when the East Rosebud River was finally designated by Congress as a Wild and Scenic River with the passage of H.R.4645 - East Rosebud Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Also, in October 2020 Senator Jon Tester introduced the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act. If the bill passes, federal agencies will be required to preserve water quality, free-flowing conditions and certain “outstandingly remarkable values” on dozens of miles of the Gallatin, Madison, Yellowstone, Boulder, Smith and Stillwater rivers and on sections of an additional 17 creeks.

The Legacy

Frank also served as a Senior Research Associate and

Adjunct Professor for the State University of New York at Albany from

1967 through 1977, presenting a series of lectures and working in the

field with graduate students in Wyoming.

In 1978 Frank's home in Moose, Wyo., burned to the ground. The fire occurred in mid-winter when the nearest plowed road access was 1/4 mile away. The fire was an immense setback to Frank's work; he had been working on a pilot study to develop satellite transmitters for use on birds with a grant from NASA, and much of his collected background data was destroyed. He also lost most of his photographs and films, and many notes and papers, but luckily his book manuscript and photographs for "Track of the Grizzly" were already at the publisher's.

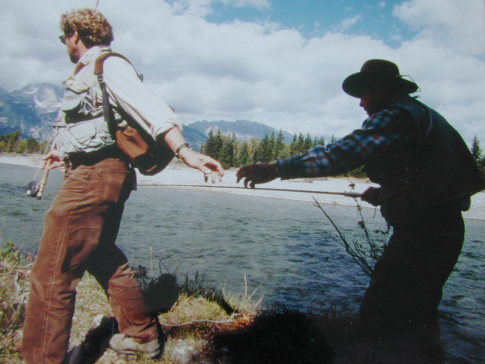

Esther died in 1980. She had been a tremendous support and a great friend to Frank, and had shouldered much of the burden of his work. Frank struggled on his own for a few years without her, but in 1987 he married a wonderful Vermont school-teacher named Shirley Cocker. Frank was officially retired, but with Shirley's help he wrote his last book, "For Everything There is a Season." Shortly after marrying Shirley, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease. This was a difficult time for him but he was determined to make the most of his waning health. He remained a scientist, making detailed observations on his symptoms. He and Shirley made several extended trips together, and they got out at every chance to hike or fish. He especially liked taking his grandchildren out to teach them the names of wildflowers. There aren't many places in the Greater Yellowstone Area that Frank didn't know. He climbed all the peaks in the Tetons in the 1940s and 1950s, explored all of Yellowstone's backcountry, and floated every stream he could. He loved to fly-fish the Snake River, to walk along its banks and observe the eagles and ospreys, to identify wildflowers, and, like his father, he could usually find a spot for a quick nap under a tree or beside a stream. Frank liked to sit on top of Blacktail Butte and watch the ravens fly. He delighted in calling to ravens to observe their reactions, and he could usually fool them into circling for another look. Even in the advanced stages of his illness he would give a raven "caw" or two from his wheelchair. His sense of humor also lasted until the end. A visiting biologist told Frank how he was inspired to study bears by Frank's work, and was answered with, "Well, as long as you feel that way we might as well conclude this interview."

With Shirley's patient and loving care, Frank was able to live at home until the last few months of his life. With her help, he went to the Lamar Valley to see grizzlies again, got out to look for birds, to hold a fly rod in his hands, and to visit friends. Frank Craighead died peacefully and joined his raven friends on October 21st, 2001, in St. John's LivingCenter. He is survived by his wife Shirley Craighead, and children Lance Craighead with wife April, Charlie Craighead with children Cooper and Andrea, and Jana Craighead Smith with husband Ron and children Evan and Erin. His brother John Craighead lives in Missoula, Montana, and his sister, Jean Craighead George, died in May, 2012.

In 1978 Frank's home in Moose, Wyo., burned to the ground. The fire occurred in mid-winter when the nearest plowed road access was 1/4 mile away. The fire was an immense setback to Frank's work; he had been working on a pilot study to develop satellite transmitters for use on birds with a grant from NASA, and much of his collected background data was destroyed. He also lost most of his photographs and films, and many notes and papers, but luckily his book manuscript and photographs for "Track of the Grizzly" were already at the publisher's.

Esther died in 1980. She had been a tremendous support and a great friend to Frank, and had shouldered much of the burden of his work. Frank struggled on his own for a few years without her, but in 1987 he married a wonderful Vermont school-teacher named Shirley Cocker. Frank was officially retired, but with Shirley's help he wrote his last book, "For Everything There is a Season." Shortly after marrying Shirley, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease. This was a difficult time for him but he was determined to make the most of his waning health. He remained a scientist, making detailed observations on his symptoms. He and Shirley made several extended trips together, and they got out at every chance to hike or fish. He especially liked taking his grandchildren out to teach them the names of wildflowers. There aren't many places in the Greater Yellowstone Area that Frank didn't know. He climbed all the peaks in the Tetons in the 1940s and 1950s, explored all of Yellowstone's backcountry, and floated every stream he could. He loved to fly-fish the Snake River, to walk along its banks and observe the eagles and ospreys, to identify wildflowers, and, like his father, he could usually find a spot for a quick nap under a tree or beside a stream. Frank liked to sit on top of Blacktail Butte and watch the ravens fly. He delighted in calling to ravens to observe their reactions, and he could usually fool them into circling for another look. Even in the advanced stages of his illness he would give a raven "caw" or two from his wheelchair. His sense of humor also lasted until the end. A visiting biologist told Frank how he was inspired to study bears by Frank's work, and was answered with, "Well, as long as you feel that way we might as well conclude this interview."

With Shirley's patient and loving care, Frank was able to live at home until the last few months of his life. With her help, he went to the Lamar Valley to see grizzlies again, got out to look for birds, to hold a fly rod in his hands, and to visit friends. Frank Craighead died peacefully and joined his raven friends on October 21st, 2001, in St. John's LivingCenter. He is survived by his wife Shirley Craighead, and children Lance Craighead with wife April, Charlie Craighead with children Cooper and Andrea, and Jana Craighead Smith with husband Ron and children Evan and Erin. His brother John Craighead lives in Missoula, Montana, and his sister, Jean Craighead George, died in May, 2012.

Frank's non-profit corporation was officially registered with the Internal Revenue Service in 1964 as the Environmental Research Institute. The name was later changed to the Craighead Environmental Research Institute and then shortened to the Craighead Institute.